The name for a community of singers that developed in Europe from the Middle Ages onwards is derived from the chorus of ancient Greek theater. From the Latin church music sung since late antiquity, which was collected and standardized under Pope Gregory I as Gregorian chant, a purely unanimous chant, the first polyphony soon emerged. The Renaissance brought forth complex types of polyphonic a cappella movements, which in the course of the 16th century reached their climax in the form of multiple choirs, which enabled new sonic experiences by juxtaposing several choirs in the (church) area. The choir became increasingly functional, especially in opera, cantata and oratorio. With the late baroque, that stage of development was reached that defines today’s understanding of choir: a permanent choral ensemble, clearly separated from the instrumental ensemble (the orchestra); Works of predominantly spiritual content with Latin, but increasingly also national language texts; increasingly in a representative character. The first civil choir associations of the 19th century, forerunners of today’s Philharmonic Choirs, made ensembles available on a scale that were able to compete and collaborate with the symphonic orchestras. In the choir, spiritual and secular, national and ideal, reactionary and revolutionary content could be expressed in a striking way; in independent compositions, but also in the choir numbers removed from a larger context. The combination of popular, seldom related, but rather impressive sounding pieces (in a musical context, this is not referred to as an anthology, but more often as a Florilegium) emerged in the course of the 19th century and continues to determine the concert programs to this day.

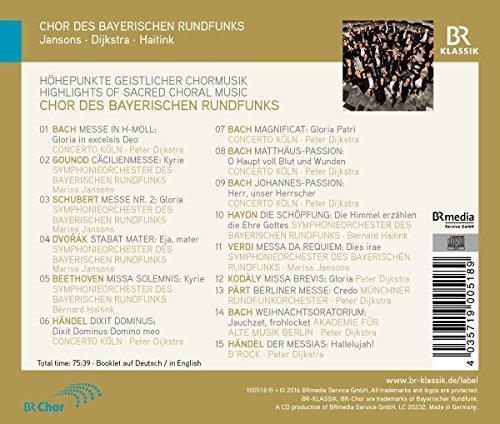

The Bavarian Radio Choir introduces itself here with the highlights of sacred choral music from the baroque period to modern times. After three hundred years, Bach and Handel’s great oratorio choirs are as lively, lifelike and gripping as they were back then. Haydn managed to preserve this for the church music of the period of the Viennese Classic, the climax of which was reached with Beethoven’s Missa solemnis. Schubert’s intimate mass compositions are examples of early German Romanticism, Gounod’s Cäcilienmesse as one for the French and Dvo ák’s Stabat mater as one for the Bohemian Romanticism of the middle and late 19th century. Verdi’s famous Messa da Requiem testifies to the close connection between Italian opera and Italian church music. The mass of the Hungarian Kodály, created immediately before the end of the Second World War, is still completely rooted in the late Romantic musical language, while the Estonian composer Pärt also cultivated the characteristic tintinnabuli style in his Berlin mass, which was created shortly before the end of the 20th century, which inspired his work defining formative. The cross-section of well-known and partly less well-known choir numbers spans a period of almost three hundred years; it shows impressively what constitutes the special character, the special aura of choral music, what has changed over the course of time and what has remained similar. And it testifies to the unique choral culture of the Bavarian Radio Choir, the crystal-clear sound, which has been praised again and again in the highest tones, and the immense plasticity of the lecture and the highest artistic quality of the interpretations.